Inside the Factory - Season 9

Season 9

Paddy McGuinness and Cherry Healey hit factory floors across Britain for a snoop around their supersized production lines. What are the secrets behind our supermarket staples?

Episodes

Chocolate Seashells

Paddy McGuinness is fully immersing himself in the festive spirit as he explores a huge chocolate factory in Belgium. With lots of taste tests to enjoy along the way, he embraces the fantastic processes and surprising science that enable the epic production lines to knock out four million individual chocolates every day. And they're especially busy in the run-up to Christmas.

Paddy is at the Guylian chocolate factory, on the outskirts of the very Christmassy-sounding city of Saint Niklas in Belgium, to learn how they produce chocolate seashells ready for the Christmas rush. He begins by meeting Kevin Stevens at the factory's intake bay to welcome in a bumper delivery of hazelnuts from Turkey. Kevin tells Paddy that the hazelnuts are a key component in the praline filling inside each of the chocolate shells.

Once the sacks of nuts are safely inside the warehouse, Paddy is chuffed to learn that the size of the nuts is very important. They must be between 8 and 11 millimetres; any bigger and they'll be too fatty, any smaller and they'll be too dry. Luckily, Paddy's nuts make the grade, and he follows 7,500 kilograms of them inside the factory.

Resplendent in his factory hairnet, Paddy's next stop is the intriguingly named Kettle Room. As he enters, he is blown away by the delicious smell and intrigued by the traditional-looking machinery. With the help of an automated shoot, a torrent of hazelnuts and refined white sugar cascades into one of six copper kettles. The kettles are heated to around 140 degrees Celsius, which roasts the nuts to draw out their subtle flavours. At the same time, the sugar caramelises. The result is a beautifully sweet, nutty mixture. The problem is, it's too chunky to be anywhere near a smooth praline paste. To solve this, the mixture is sent through a mincer, which produces a fine crumb with a melt-in-the-mouth texture. Paddy is in heaven in his first of many taste tests. Then things get even better, as milk chocolate is added to produce a velvety smooth hazelnut praline.

With the centre of his chocolates made, Paddy is guided to the enormous, automated seashell production line. Two thousand six hundred moulds in the shape of different seashells continuously travel through the line. As they make their way along, half receive a splash of white chocolate and half a splash of milk chocolate, then an additional layer of chocolate is added to create the marbled effect that the finished chocolates are known for. In a surprising twist, each and every mould is flipped upside down, letting the chocolate pour out. But Paddy needn't worry; it's all part of the plan to ensure the perfect amount of chocolate is left in the moulds to create the outer shell. After travelling through a cooler, it's time for the hazelnut praline that Paddy helped to make earlier. Eighty-eight taps gently release an average of 6.8 grams of the praline filling into each half of the chocolate shells. Then, to complete the seashell shape, the two moulded halves are joined together. Just three hours and five minutes after the start of production, Paddy delights in the sight of finished chocolate seashells streaming past him, and he can't help but get stuck into one - or two!

As the final act of this sweet Christmas drama draws to a close, the chocolates head to the packing area, where they're dropped into blister packs and then slid inside cardboard boxes and sent to the dispatch area. And because the site is so large, there's only one way to get there – by bicycle! The six-year-old Paddy couldn't have dreamt of a better Christmas present: riding a bike through a chocolate factory.

Four hours and twenty-five minutes after the start of production, Paddy waves off a lorry load of chocolate from one of the loading bays. From the factory in Belgium, the seashells head off all over the world. But it's the Brits who eat the most at Christmas, putting away a whopping 44.7 million chocolate shells over the festive period!

Elsewhere in the episode, Cherry is also in Belgium, at another massive chocolate factory, learning how they produce the white chocolate used in Paddy's chocolate seashells. And she enlists the help of mathematician Bobby Seagull to explore the art, or rather the maths, of Christmas tree decoration.

And historian Ruth Goodman is in Belgian too, exploring how Belgian chocolate has become world-famous, and she delves into the European origins of Santa Claus.

Sliced Bread

In a nostalgic episode of Inside the Factory, new presenter Paddy McGuinness visits the Warburtons bread factory in his hometown of Bolton, where he once worked as a youngster more than 30 years ago. At Warbies, as the locals call it, he catches up with old friends and learns how the machines, ovens and conveyors he once cleaned enable the site to produce 1.4 million loaves of bread every week.

As a fitting return to the factory, Paddy makes a grand entrance by driving a tanker of flour through the gates. As he manoevres his way to the intake area, he reveals that he was a young boy of sixteen when he worked here - it was a Saturday job, cleaning out the massive bread-making machines. However, the machines didn't run on Saturdays, which means that he's going to see them in action for the first time! With a little trepidation, Paddy dons the obligatory hairnet and steps inside the factory to soak up the memories. But he can't hang around reminiscing - there's sliced white bread to be made.

So, he heads back outside to where he left his tanker full of flour. Head of Flour Stuart Jones tells him that they receive three tanker loads each day, containing a total of 90 tonnes – enough to make 170,000 loaves of bread. As the mix of British and Canadian flour is unloaded, Paddy heads back inside the factory, where he spots a familiar face - his old school friend Pete, who got him the Saturday job and still works at the factory.

After a quick chinwag, Paddy heads to the dough-mixing area to meet someone with a very impressive title: Unbeatable Quality Manager, Rachel Bacon. Rachel tells Paddy that the key to making the best white bread is air bubbles; inside each slice there are 13,000 bubbles, which are all counted by computer. To make the dough, a mixer combines the flour with water and brine, along with yeast and a special ingredient called improver, which helps with the structure of the dough.

After mixing for three minutes, the dough is tipped out and chopped into 341 separate pieces, each one weighing 920 grams. Every one of these mounds of dough will go on to make a loaf. The dough travels through a machine, which relaxes the strands of gluten inside and allows them to fully form, holding in the thousands of bubbles.

Next, the dough is flattened and rolled out again - a bit like a Swiss roll. Then it's chopped into four, turned 90 degrees and squashed together again. This method is called cross panning and gives extra strength to the finished loaves. Paddy and Rachel agree that it's an important process, as it means that when you have a chip butty and want to roll the bread around the chips, it won't break.

Paddy's dough drops into tins and travels towards a huge machine called a prover, where Paddy meets another expert, Manufacturing Excellence Manager Joanna Whitehurst. This massive, warm room is kept at between 37 and 40 degrees Celsius, which is the perfect temperature for the yeast inside the dough to activate and feed on naturally occurring sugars - a process called fermentation. This releases carbon dioxide gas, causing the bubbles in the dough to expand and the loaves to rise. Once risen, a lid is placed on top of every tray, which gives the loaves a distinctive flat top.

After two hours and forty minutes in production, the tins go into the 32-metre-long oven. Paddy tells Joanna that when he worked at the factory, he used to clean the ovens - and they were spotless! Twenty-one minutes after entering the oven, the bread is turned out of the tins, and the golden loaves stream along the conveyor for Paddy to see and smell them in all their glory.

They are making sliced bread, so the slicing machine creates 17 slices for every loaf, each one is 13.7 millimetres thick. Finally, they are wrapped in traditional-style waxed paper, which helps to lock in the freshness. Paddy remembers his mother using the distinctive paper to wrap his sandwiches for school.

As he heads to dispatch, Paddy bumps into his old mate Pete again. They reminisce about the old days at the bread factory. Paddy remembers not being able to get out of bed in the morning but having to walk to the factory in the cold and rain, ready to start his shift at 6.00am. Paddy watches as 6,000 loaves are loaded into the back of a lorry; the factory dispatches 44 wagons every day.

With the soundtrack of M People's 90s anthem Moving on Up blasting out, Paddy loads the final trolley of sliced white bread into the lorry. Elsewhere in the episode, Cherry Healey visits the Dualit factory to learn how they make toasters and visits a brewery turning waste bread into pints of beer, while historian Ruth Goodman discovers why white bread was banned during the Second World War.

Cheese Curls

In this episode, Paddy McGuinness explores the secrets of the Walkers factory in Lincoln, to reveal how it makes 500 million packs of Quavers every year.

Paddy begins by meeting factory manager Layla Whiting, who reveals that, despite popular belief, cheese curls aren't officially classed as crisps! In fact, while crisps are made from sliced potatoes, Quavers are made from the potato starch powder left behind during the crisp-making process. Their first stop is a huge mixer where the starch powder is added, along with equally fine rice and soya flours. Then they add some mild seasoning of salt, pepper, onion powder and yeast - but no cheese flavour yet. The whole lot is mixed with water to create a dough.

This is a huge and very hot factory! Comparing it to getting off a plane on holiday, Paddy exclaims, ‘this is like landing on the sun!' But he soldiers on to the next stage of production. After mixing, the dough is forced under very high pressure through an extruder, emerging as a continuous one-millimetre-thick sheet. It looks more like a lasagne sheet at this stage and the process is nothing like Paddy imagined it would be.

To ensure every one of the snacks ends up with the famous curly shape, the dough is stretched over rollers to add tension. Then it travels through an 18-metre-long steamer, increasing the moisture level in the dough to 40%, making it more pliable and stretchy. After being quickly cooled, the continuous sheet of dough is sent rushing through a machine which chops it into 13 millimetre by 40 millimetre pellets, at a rate of 7,900 a minute. But the pellets contain too much moisture, so they are sent through a series of dryers, bringing the moisture content down to 11%.

Over in the frying area, Paddy learns how 1.2 tonnes of pellets travel through a specialist fryer every hour. Inside the fryer, the pellets are plunged into sunflower oil heated to 200 degrees Celsius. The heat of the oil causes any remaining water inside to turn to steam, puffing them and leaving tiny air holes. At the same time, the tension created when the dough was stretched now contracts and curls up. After twenty seconds in the oil, 1.8 million perfectly-formed curls cascade out of the fryer every hour. Finally, Paddy is able to see the curly snack he knows. There is one vital thing missing from the snacks though – cheese flavouring. To put that right, each one of the freshly cooked curls travels through a huge metal drum where a precise amount of cheese powder flavouring is applied.

After a welcome taste test, Paddy follows his snacks, still warm off the production line, to the packing department. First, a specialist machine called a multi-head weigher carefully portions out 16 grams of cheese curls before another machine seals them neatly into aluminium and plastic packets. Then, each packet is sent hurtling towards a robot which sorts them into groups of six, before they are packed into multipack bags.

Finally, the multipacks are put into boxes and placed on pallets before making their way to the dispatch area. There, Paddy learns how 93,600 packets are loaded onto each waiting lorry, before being sent to shops and supermarkets across the country.

Earlier in the episode, Cherry visits a Walkers crisp factory to learn how the starch from potato crisp production is transformed into the potato starch powder used to make the cheese curls. And she visits another factory in Leicester to find out how ten million bags of Bombay Mix are produced every year.

Meanwhile, historian Ruth Goodman learns how a group of American military scientists invented cheese flavouring during the Second World War.

Flapjacks

Paddy McGuinness visits the Graze factory in west London armed with his trusty tasting spoon to learn about the process that creates 40 million flapjacks a year and the science behind their sticky toffee flavour. Cherry Healey learns how oats can benefit gut health and Ruth Goodman savours the history of Staffordshire oatcakes and golden syrup

Hardback books

Sausage rolls

Paddy McGuinness visits a factory in Northern Ireland producing sausage rolls on an epic scale.

Recently Updated Shows

MobLand

With the most powerful clients in Europe, MobLand will see family fortunes and reputations at risk, odd alliances unfold, and betrayal around every corner; and while the family might be London's most elite fixers today, the nature of their business means there is no guarantee what's in store tomorrow.

MobLand follows two generations of gangsters, the businesses they run, the complex relationships they weave and the man they call upon to fix their problem.

Daredevil: Born Again

Matt Murdock finds himself on a collision course with Wilson Fisk when their past identities begin to emerge.

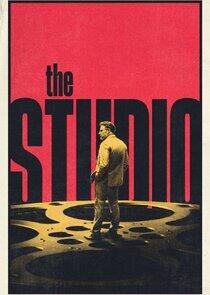

The Studio

As movies struggle to stay alive and relevant, Matt and his core team of infighting executives battle their own insecurities as they wrangle narcissistic artists and craven corporate overlords in the ever-elusive pursuit of making great films. With their power suits masking their never-ending sense of panic, every party, set visit, casting decision, marketing meeting, and award show presents them with an opportunity for glittering success or career-ending catastrophe. As someone who eats, sleeps, and breathes movies, it's the job Matt's been pursuing his whole life, and it may very well destroy him.