The Life of Mammals - Season 1

Season 1

Episodes

A Winning Design

David Attenborough looks at why mammals are the most successful creatures on the planet. Here he visits Australia and South America to study the lives of marsupials and then moves on to mammals such as humans, who develop their young in wombs rather than pouches.

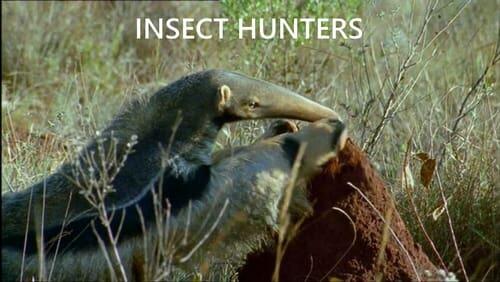

Insect Hunters

David Attenborough looks at the mammals that hunt insects. These creatures shared the planet with the dinosaurs, but when the giant reptiles disappeared they seized their chance to conquer new territory. David meets moles that swim through sand, a shrew that hunts underwater and another that sprints down polished running tracks so fast that most predators can't catch it.

Some ancient insect hunters are surprisingly familiar. In his garden in London, David watches the seemingly painful act of hedgehog courtship.

Giant anteaters and pangolins are less familiar, and perhaps the most bizarre-looking mammals on the planet. David meets a giant anteater first-hand. It may be dim-witted, but it also has the longest claws of any mammal - and the longest tongue too, which is just the job for a diet made up exclusively of ants and termites.

Many insects can fly and are out of reach for ground-dwelling mammals, but early in the mammals' history, probably when the dinosaurs still roamed, the insect hunters took to the air. Spectacular aerial photography at night shows how these bats catch their prey, including one British bat - the natterer - that catches spiders from their webs without getting tangled in the silk.

David takes his story full circle when he meets the world's strangest bat in New Zealand. When darkness falls, the bat drops to the ground, folds up its wings and hunts insects like a shrew.

Plant Predators

Some of the biggest predators to walk the earth face a constant battle - their prey is heavily armoured, indigestible and sometimes even poisonous. What makes this struggle more remarkable is that thesepredators do not prey on animals - but on plants.

The first great battle that plant predators must fight is with their prey. Plants arm themselves with deadly poisons, but plant predators are not deterred. The elusive tapir of the South American jungle visits secret clay licks in search of a natural antidote. The pika, the 'rubble rabbit' of the Canadian Rockies, even makes poisons work to its advantage, exploiting them as a natural preservative.

Sometimes, the problem is not what is in your food, but what is not. By bugging the caves of Mount Elgon, the crew reveals startling images of underground elephants mining for salts deficient in their green diet.

The next great battle that plant predators face takes place on the open plains, as behind every plant eater lurks a meat eater. See the hunt from the plant predators' point of view, equipped with wrap-around vision, ears that rotate 360 degrees and elongated limbs that make it harder for them to be caught than most wildlife films would suggest.

Plant predators are themselves equipped with dangerous weapons, used in the greatest battle of all - with each other. Witness the drama of the annual bison rut in the Badlands of North America, discover the secret of the battering rams of the big-horned sheep of Canada, and analyse the fighting technique of horned animals as they ram, wrestle and stab their opponents.

Amazingly, all of these extraordinary behaviours stem from the apparently simple act of eating leaves.

Chisellers

Rodents like rats, mice and squirrels are the most numerous mammals on the planet. This programme reveals how, with their constantly growing, chisel-sharp front teeth, they are specialists in breaking intoseeds. It also shows how they have adapted this talent to help them make their homes and even live underground, as well as revealing their ability to store food - and their ability to breed prolifically.

In Panama, David Attenborough fails to smash open a tropical nut with a large rock. Yet the terrier-sized agouti can easily gnaw through the concrete-hard casing to get at the nutritious kernel inside.

Like several rodents, the desert kangaroo rat stuffs seeds into its cheek pouches to take back to its burrow for safer eating, while the strange-looking naked molerat lives its entire life underground, using its massive incisors for digging tunnels and ripping apart buried tubers for food. Beavers can even cut down trees with their front teeth, using the logs for building their dams and lodges. A tiny infrared camera inserted into a beaver's lodge shows how they stay active during winter, feeding on the leaves and branches they stored under the ice in autumn. But unknown visitors also reveal themselves on camera - a family of muskrats sharing the lodge, tolerated perhaps in exchange for a regular supply of fresh bedding for the beavers.

Rodents are known for being prolific breeders. In Australia, this can cause such plagues that farmlands and homes are literally overrun by carpets of running mice. The largest rodent in the world, the capybara, also occurs in huge numbers, but they live in the vast swampy grasslands of South America so there is plenty of room to graze in great herds.

Meat Eaters

Join Sir David Attenborough in the fifth programme in the series, as he sits beside wild lions in the darkness of the night and meets a Siberian tiger face to face. From the first tree-dwelling hunters through to the modern-day big cats, we follow the true story about cats and dogs to find out what you need to be a true carnivore.

In the frozen north, the Arctic fox needs to hunt during warmer times and cache this food to survive the winter. In southern climates, leopards and tigers have become solitary hunters relying on stealth and surprise to catch their next meal, coming together only to mate. Others around the globe like wolves and lions work in teams and family groups so they can tackle larger prey and better protect their young. But their efficiency as hunters makes it essential that their family life is held together and tightly controlled. With all hunters, the aggression of the kill means the difference between life and death.

Opportunists

David Attenborough meets the omnivores - the opportunists. When it comes to food, this diverse range of animals, which includes grizzly bears at one end and rats on the other, are so adaptable that they can always make the most of whatever happens to be around at the time. They are nature's generalists but each is equipped with some very specialised skills.

North American raccoons use the same proportion of their brain for processing information from their hands as humans use for sight. Indeed, a raccoon's sense of touch is so acute that, in a way, they can see with their hands, making it easy for them to find food in murky streams at night.

The rare and bizarre-looking babirusa from Sulawesi is equally capable at finding food but uses another part of its body - its nose. This pig's legendary sense of smell enables it to locate the smallest amount of fallen fruit in its dense forest habitat.

Omnivores are able to exploit the most extraordinary opportunities, whether they be man-made or those found in the wild. In Texas, skunks descend into bat caves where the atmosphere is thick with ammonia and lethal fungal spores (and the carpet of flesh-eating beetle larvae) and, in the pitch blackness, they feed on baby bats that have fallen off the cave ceilings.

And if there is no food, some omnivores are able to hibernate, like the raccoon dog, which can double its weight in five months of summer. It is a trick that is also taken up by one of the most impressive of all mammals, the grizzly bear. David gets close to these bears and follows their short season of plenty. He explains how they manage to gain enough weight to survive half a year without food.

The story of the omnivores would not be complete without reference to the most successful of all, the humans. As an example of this success, David looks at the Kumbh Mela festival in central India.

Return to the Water

From the roughest seas to the crystal clear waters of the Florida springs, David Attenborough swims with sea otters and dives with manatees, as he follows those mammals who, millions of years ago, left dry land and returned to the water to feed.

Attenborough races across the Pacific Ocean to find the largest mammal that has ever lived on this planet, the blue whale, a hundred feet long. As David says, 'nothing like that can grow on land because no bone is strong enough to support such bulk. Only in the sea can you get such huge size as this magnificent creature'. He also bounces through the waves off New Zealand to witness an enormous pod of high-speed dolphins pursuing their fish dinner.

Although some marine mammals like seals and sea lions still come ashore to breed, all porpoises, dolphins and whales have evolved to court, mate and give birth in the water. Indeed the sight of humpback whales mating is truly amazing, with the males wielding the longest penis in the animal kingdom - twelve feet long - and so highly mobile that it can seek out the female genital opening as she swims alongside.

Life in the Trees

David Attenborough meets the tree dwellers - those mammals that have adapted to a life at height. Some, like meerkats, might hardly seem to qualify but they do regularly climb small trees to scout for danger. Others, like gibbons, live 100 feet or more above the forest floor and never descend to the ground.

One third of the world's surface is still covered by forest of one kind or another and mammals from a diverse range of groups have exploited them all.

Climbing requires some very specialised adaptations. Hyrax have moist, rubbery feet to help them negotiate slender branches, sun bears rely on sharp claws and strong forearms, coatis go one step further with sharp claws and a long tail for balance. And, when it comes to tails, there's another very effective design. Tamanduas, arboreal anteaters, have gripping tails, which leaves their hands free to break into termite mounds.

But climbing into a tree is just the start. The real challenge is how to move between trees. Grey squirrels cope with small gaps by jumping, a technique favoured by many primates as well as bush babies and lemurs. The latter can leap thirty feet in one go but there are other tree dwellers that can travel further than that. By stretching out a membrane between front and back legs, flying squirrels can glide three times that distance, while fruit bats, along with their insect-eating cousins, are the only mammal to have developed powered flight and their strong wings enable them to fly as much as 30 miles in a night in their search for fruiting trees.

Life in the Trees is full of strange and unfamiliar animals, such as the Indian slender loris and the fossa, Madagascar's largest arboreal predator, both filmed for the first time in the wild. In this programme, David gets close to many of them, and for some this meant climbing high into the canopy himself.

Social Climbers

In the penultimate episode, David Attenborough looks at monkeys. This group started its life in the tree-tops and this is where we join the capuchin, whose acute vision and lively intelligence helps them findclams in the mangrove swamps of Costa Rica and crack them open on tree-anvils. The swamps are also full of biting insects, but the monkeys rub themselves with a special plant that repels them.

In the forests of South America, we see how different species of monkey can live alongside one another by having slightly different diets. The saki is a living nut-cracker, the spider monkey uses its tail to reach the ripest fruit and the pygmy marmoset is so small that even the outermost twigs of the canopy can support its weight as it stalks insects. David even meets an owl monkey, a shy and mysterious creature with huge eyes that feeds at night to avoid competition with the others.

Hanging from a rope high in the forest canopy of Venezuela, David watches the stunning red howler monkey as it uses excellent colour vision to pick the best leaves. Although colour vision evolved to detect leaves and ripe fruit, it allowed the monkeys to become the most colourful of all mammals. The scarlet face of a uakari is dazzling, the long moustache of the emperor tamarin is striking even from a distance, but the most beautiful colours are found on the guenons of west Africa that use intricate patterns on their faces to send social messages.

These guenons are under constant threat from eagles, leopards and chimps, but different types of guenon join forces with other monkeys. They travel together in an extraordinary anti-predator alliance based on shared vigilance and a remarkable degree of vocal communication.

But the most complex relationships to be found in the monkeys are between animals living in the same group. And the larger the group, the more individuals with good social skills will thrive. In Sri Lanka, we watch male toque macaques battle for mates and see how brain can triumph over brawn.

Ten million years ago, a change in climate allowed one group of African monkeys to move down from the trees and on to the grasslands. But living on the ground brought an increased risk from predators, forcing baboons to live in even larger groups - and this put an even greater emphasis on social skills. Life on the ground also opened up new hunting opportunities - the hapless flamingos of Kenya are now on the menu.

Several miles above the savannah, in the highlands of Ethiopia, we meet the monkeys that live in the largest groups of all - geladas. Groups of 800 drift across the high plains like herds of wildebeest. It is hard for so many animals to stay in contact by grooming, so these monkeys have another way of communicating - they chatter to each other using the most complex sounds made by any mammal yet studied, except for ourselves. So while monkeys in the treetops have rich and varied social lives, it is those that came down to the ground that developed the most complex and communicative societies of all - a fact not without significance for our own ancestry.

Food for Thought

David Attenborough concludes his documentary series with a programme about our closest animal relatives, the intelligent great apes, and finds out how their large brains enabled one of their kind, an upright ape, to go on to dominate the planet. David travels to the forests of Borneo to meet a remarkable orangutan with a passion for DIY and a talent for rowing boats. He shifts continent to Africa and takes part in a special nut-cracking lesson with a group of chimps learning survival skills. He discovers how food - and the ways apes find it - has been key to the evolution of our large brains.

Filmed for the first time, the chimps of Ngogo hunt down monkeys to supplement their vegetarian diet with meat. Our ancestors must have also hunted for meat, but with one crucial difference - they did so on two feet. David meets an extraordinary group of wading chimps that give us a unique window into our past, the moment when we took a step away from being apes and a step towards humanity. As soon as they stood upright, humans began to manipulate their environment, transforming the very surface of the planet by domesticating plants and animals. This most successful of all mammals has been able to increase the supply of food beyond that which occurred naturally. As a result the number of human beings could increase. David travels to the ruins of the capital of the Maya people to trace the rise and fall of an entire human civilisation. The temples of Tikal used to be the highest buildings in the Americas until the skyscrapers of New York were built. So why did the Maya civilisation collapse? Will modern city-dwellers suffer a similar fate?

Recently Updated Shows

The Ex-Wife

Tasha is living the dream: she has the perfect house, a loving husband and a beautiful little girl. But there's one large blot on Tasha's marital landscape: her husband's ex-wife won't leave them alone and seems intent on staying in the picture.

When Tasha returns home one day to find her life turned upside down, she realises that the dream she is living may be about to turn into a nightmare.

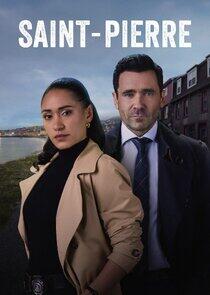

Saint-Pierre

After Royal Newfoundland Constabulary Inspector Donny "Fitz" Fitzpatrick digs too deeply into a local politician's nefarious activity, he is exiled to work in Saint-Pierre et Miquelon (the French Territory nestled in the Atlantic Ocean just off the coast of Newfoundland). Fitz's arrival disrupts the life of Deputy Chief Geneviève "Arch" Archambault, a Parisian transplant who is in Saint-Pierre for her own intriguing reasons. Saint-Pierre is a police procedural with French star Joséphine Jobert as Arch and Canadian star Allan Hawco as Fitz, and James Purefoy rounding out the stellar team. As if by fate, these two seasoned officers — with very different policing skills and approaches — are forced together to solve unique and exciting crimes. Although the islands seem like a quaint tourist destination, the idyllic façade conceals the worst kind of criminal activity which tend to wash up on its beautiful shores. At first at odds and suspicious of each other, Arch and Fitz soon discover that they are better together... a veritable crime-fighting force.